CuriosityAtPlay

Expectation Agreements: The SOP Reframe That Actually Works

I was standing in front of twenty kids, and my equipment had just betrayed me.

I was standing in front of twenty kids, and my equipment had just betrayed me.

It was a Z-Tag event—laser tag, the kind of high-energy event GameTruck coaches run every weekend. The taggers were supposed to connect to the system, each with a unique ID number. Simple enough. Except some of them had duplicated IDs, others had dropped out entirely, and now I had a crowd of increasingly impatient ten-year-olds staring at me while I fumbled through settings menus I barely understood.

I figured it out. Eventually. There’s a “re-enumerate” function buried in the settings that forces all the taggers to reconnect with unique IDs. Crisis averted. Party saved.

But here’s the thing: once I solved the problem, I knew I had to document it. And that’s when I faced a choice that changed how I think about SOPs forever.

The Documentation Trap

I could have taken the standard approach. You know the one. “The Settings Screen allows you to adjust system settings.” Thanks for nothing.

Most technical documentation describes what things are. It catalogs features. It labels buttons. It defines terms. And it sits in a binder somewhere, unread, while your team fumbles through the same problems you already solved.

I didn’t want that. I wanted my coaches to walk into high-pressure situations—twenty kids waiting, parents watching, equipment misbehaving—and know what to do.

So instead of documenting the system, I documented the success path.

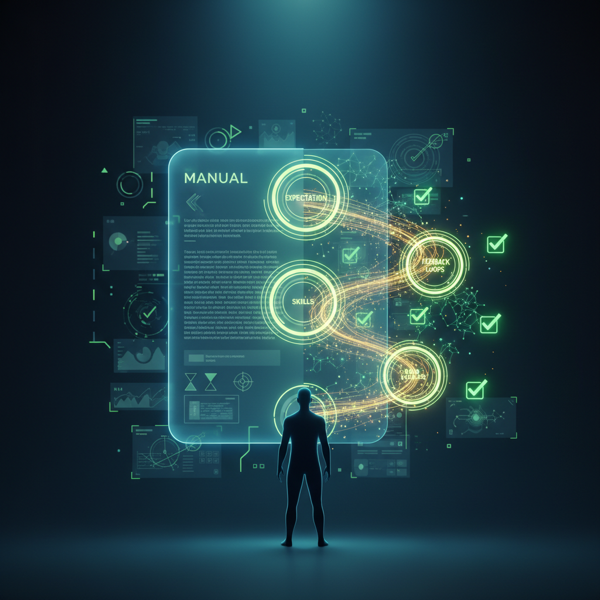

Expectation Agreements, Not SOPs

Here’s the reframe: Stop thinking of these documents as “Standard Operating Procedures.” That phrase implies compliance. It suggests behavior control. It sounds like something HR makes you sign.

Instead, think of them as Expectation Agreements—documents that answer one question: How does someone know they’re contributing well?

To answer that, you need to address three things:

1. What is expected? Not “use the settings screen correctly.” The expectation is: The coach can fix common equipment problems fast, so the event keeps running smoothly.

2. What skills, tasks, or methods produce that outcome? Navigate to the settings menu. Find the re-enumerate function. Run it. Be patient while the system cycles through. Know that most problems can be solved from the command system without panicking.

3. What feedback loops show you’re on target? Watch the taggers reconnect. Check the event screen for unique IDs. Ultimately? The real feedback is the customer tip and the NPS score after the event.

When you frame documentation this way, it stops being about technical accuracy and starts being about setting people up to succeed.

Where AI Comes In

Here’s what I’ve discovered: AI is remarkably good at helping you build these expectation agreements.

You can take a messy process—something you do but haven’t documented, or an existing SOP that reads like a technical manual—and use AI to transform it into something useful.

The key is asking the right questions. And now that you know the three questions, you can prompt an AI to help you answer them.

Here’s a prompt you can copy and adapt:

I want to create (or improve) an Expectation Agreement for a process. An Expectation Agreement answers three questions:

1. What is expected? (The outcome or result someone should deliver)

2. What skills, tasks, or methods are necessary to achieve that outcome?

3. What feedback loops help the person know if they're on target?

Here's the process I want to document:

[Paste your existing SOP, or describe the process in plain language]

Please help me:

- Clarify the core expectation (what does success look like?)

- Identify the key skills and steps needed

- Suggest feedback mechanisms so the person knows they're succeeding

Frame everything from the perspective of someone doing the work, not someone auditing it.

You can use this to analyze an existing SOP that feels stale, or to create a new one from scratch. Either way, the AI will help you think through the three questions—and you’ll end up with something your team might actually use.

Why This Matters

Great documentation isn’t about covering your bases or creating a paper trail. It’s about helping people succeed before problems happen.

When I was standing in front of those twenty kids, I needed to already know what to do. Not figure it out live. Not call someone. Not dig through a manual that described what every button does without telling me when I’d need it.

Your team is in that position every day. Maybe not with laser tag equipment, but with processes, tools, and situations where they need clarity in the moment.

The question isn’t “Do we have an SOP for this?”

The question is: “Does our team know how to succeed?”

Your Homework

Pick one process in your business—something that matters, something that causes friction when it goes wrong.

Ask yourself the three questions:

- What’s the real expectation? (Not the task, the outcome.)

- What skills or methods does someone need to deliver that outcome?

- How will they know they’re on track?

If you can’t answer those questions clearly, neither can your team. And that’s not a training problem—it’s a documentation problem.

Use the prompt above to get started. Let AI help you build something people will actually read.

Scott Novis is the founder of GameTruck and an accountability coach for the Entrepreneurs Organization (EO) Accelerator program, where he helps small business owners build systems that set their teams up for success.

250617 - Knowledge Disruption

Everything you Know About Emotions is Wrong

One of the most interesting books I have read in the past few years was Journey of the Mind by Ogi Ogas. This book gave a very simplified explanation of the work of Stephen Grossberg. Grossberg’s work, admittedly, is really dense, and he cites his own research quite a bit. However, the concepts he puts forward are amazing, especially because much of his early work inspired other engineers and scientists to create the kinds of neural networks and learning systems that created generative AI— the software that is changing our world.

The reason I am enjoying the book How Emotions Are Made by Lisa Feldman Barrett is that her work to a large degree supports some of the key concepts put forward by Grossberg and Ogas. Namely, our brains operate differently than we think.

You have no doubt heard that the amygdala (that little walnut-sized part of your brain buried deep inside your “lizard brain” at the top of the spinal column) is responsible for “fear.”

Feldman’s meticulous research has revealed that this just isn’t so. In particular, I love her work because she has undertaken the daunting task of trying to reverse almost a hundred years of scientific misconception. And if there’s one thing science, academia, and most humans love to do is latch onto an idea and hold it for dear life.

Adam Grant pointed this out beautifully in his book Think Again. Instead of actually rethinking or reconsidering flawed ideas, nearly all humans have a playbook we run instead. In various orders, in various ways, we run through three “personas” in rapid succession. We will take on the role of:

- Preacher— extolling the virtues of our threatened belief.

- Prosecutor— pointing out the flaws of the new belief.

- Politician— we will pander to other believers and try to rally their support against the new idea.

It appears to be part of the human condition of achievement and leadership, that when you climb to the pinnacle of any area that holds influence over others, you want to establish a “realm” and defend it. Not all realms are political or physical. Some are ideological. And according to Dave McRaney, these are non-trivial. We find safety in groups. In his book How Minds Change, he could not find a single instance of a high-profile “change of mind,” where someone who was a card-carrying member of a controversial community changed their mind then left the group. In fact, the opposite happened. They had to leave the group first. And only after they felt safe and supported were they able to reconsider the beliefs, thoughts, and opinions they held for so long.

We love disruption in industry, but not so much in ideas, beliefs, and knowledge. We crave certainty. We want to know. So for me, the most impressive part of Feldman Barrett’s work is the uphill battle she is facing trying to reveal the misconceptions we have held for decades, and in some cases millennia, about what emotions are, how they are formed, and how we perceive them.

That is no small task. And what’s the punchline? The amygdala is not responsible for fear. It is a part of a very complex system that is responsible for generating all of our emotions. The idea that there are parts of the brain dedicated to certain emotions is, what I would call an “organistic” view of the brain, that certain “circuits” are dedicated to do certain things, like the organs of the body are organized to perform certain clearly identifiable functions such as lungs for breathing, stomach for digestion, heart for circulating the blood. But the brain is different. To say some dedicated part of the brain is responsible for creating emotion is like saying some part of the silicon on the computer chip inside your phone is responsible for running your texting application, and only that part. That’s all it does. Clearly, the central processing unit (CPU) in your phone runs ALL the software on your phone, every app, in addition to running an operating system that is always active.

The human brain is not so different. I love Feldman Barrett’s analogy that the brain is like a sports team. The roster is bigger than the number of players on the field, and depending upon the situation in the game, different players may be on the field, some go in, some leave, a few stay most of the time, but when the game was over we say “the team won.” Well, who actually did the winning? Nearly everyone contributed to the win, some more than others, but on a different day it could change yet again. The brain works like this, with different systems contributing in different amounts, often to produce the same or similar outcomes.

Her big finding is that emotions are constructed much like thoughts or memories. How we experience emotions, as to thoughts might be another thing, but there is no one “fear circuit” in the brain centered on the amygdala or elsewhere. The amygdala plays a part in lots of emotions, and seems to have more to do with novelty and cue detection than only fear processing.

Which Requires More Discipline?

Which is harder? Doing something you don’t want to do, or resisting a temptation to do something you know you shouldn’t do.